Meta-learning for Biomedical Image Analysis and Health Informatics

Introduction

Deep Learning Problem

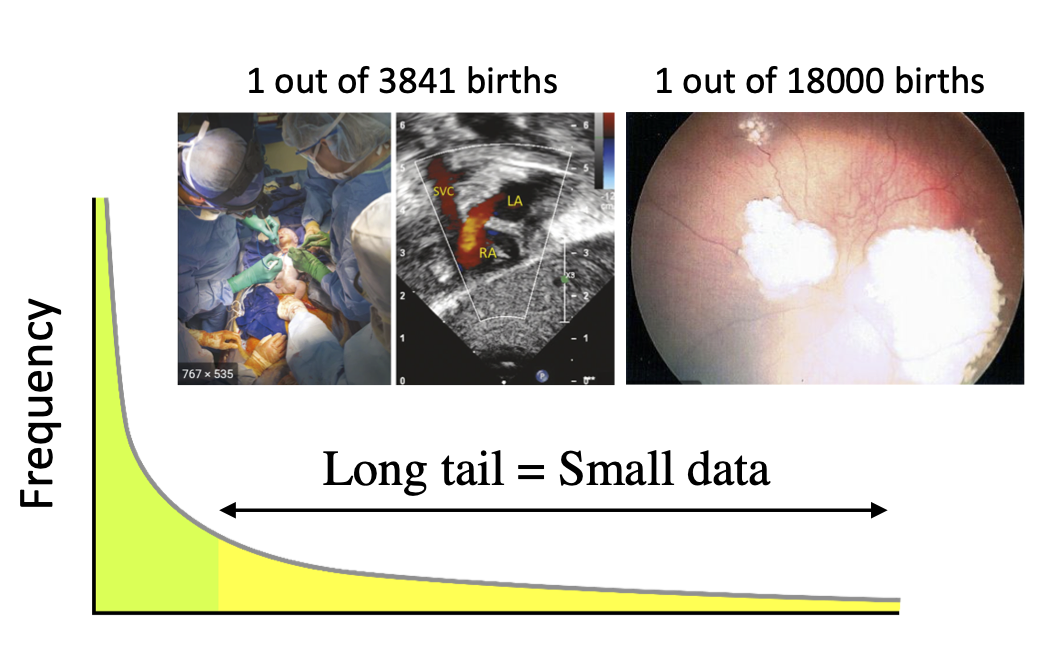

Deep neural networks have become state-of-the-art approaches for various clinical tasks, including skin cancer classification 1, diabetic retinopathy detection 2, macular degeneration detection 3 and lung cancer screening 4. However, these performances come at the cost of vast quantities of labeled data for training the deep learning models. For example, around 60000 retinal images were used to train the model to assess the severity of age-related macular degeneration 3. And the lung cancer screening model 4 was developed based on the NLST dataset which consisting of 42,290 CT cases from 14,851 patients. Obtaining a large labeled training dataset is not an easy task in the medical field and there are several reasons. First, unlike natural images labeling problem which can be largely relieved by crowdsourcing services, medical image analysis can be quite complex even for trained professionals as it requires intricate understanding and thorough examination of image details. Therefore, the labeling process can be expensive and inefficient especially for experts who need to work at the front line at the same time. Second, privacy concern of losing patient privacy and sensitive information prevents the data sharing between multiple institutions, making it more difficult to collect a large dataset for research purposes. Third, certain diseases are rare by their nature. For example, as shown in figure 1, 1 out of every 3841 births would suffer from hypoplastic left heart syndrome and 1 out of every 18000 could have retinoblastoma. Rare diseases like these close the door of large-scale training.

Methods For Few-shot Problem

Three main different underlying principles can be used to address this issue. First is to use data augmentation techniques or generative model, which try to directly increase the number of training samples. The concern of this type of approach is that the generated data always requires validation to avoid out-of-distribution samples that may negatively affect the performance of the model. The second way is to use active learning to select the most informative samples to label, so that the ``Return On Investment” can be maximized. The drawback of this is that it requires the involvement of the expert labeling and the amount of labeling effort to be invested varies from different applications. Finally, transfer learning allows the model to adapt to new tasks by using its previously learned knowledge, often reducing the amount of data needed for generalization. However, transferring knowledge always requires at least two tasks/datasets, which inevitably introduces the covariate shift or dataset bias problem, caused by the difference in the conditions, or domains, under which the systems were developed and those in which we use the systems. In medical imaging, images acquired at different sites can differ significantly in their data distribution, due to varying scanners, imaging protocols, or patient cohorts. Fine-tuning is a common approach to mitigate the impact of this dataset shift problem, but when we have limited samples from the target dataset, fine-tuning does not work well. Moreover, this approach require taking the system offline which can incur a significant delay. This is where meta-learning can help.

What Is Meta-Learning

Meta-learning falls into the transfer knowledge principle to solve the data scarcity problem. Meta-learning aims to study how meta-learning algorithms can acquire fast adaptation capability over multiple learning episodes - often from a collection of related tasks - and uses it to improve its future learning performance 5. Meta-learning is trying to align with human learning, where the human can learn from many tasks and keeps updating its learning strategy, so it is also called “learning to learn”. It can be applied to both multi-task scenarios where task-agnostic knowledge is extracted from a task distribution and used to improve the learning of new tasks from that family 6; and single-task scenarios where a single problem is solved repeatedly and improved over multiple episodes 7. Meta-learning can not only reduce the dependency of deep learning systems on data but also largely reduce the learning time when it is adapted to the new task. It in general has better generalization ability and can adapt to \emph{unseen} data. This is in contrast to transfer learning and domain adaptation which require (supervised or unsupervised) data from all tasks to be available in the training phase. Meta-learning has achieved success in a variety of problems such as few-shot image classification 6, unsupervised learning with task generation 8, meta-reinforcement learning (RL) 9, hyperparameter optimization 7, and neural architecture search 10.

Importance of Meta-learning in Medical Area

Why is meta-learning important in biomedical image analysis and health informatics? Medical data is characterized by significant distribution shifts and small sample sets that negatively affect the quality of the generated model. For example, in the cell classification task 11, there are several contributing factors for poor generalization; different biomarkers, unique cell morphologies, variations in stain intensity, and image quality all contribute to the variability of the data. Each of these factors could be considered a unique parameter with which to create unique classification tasks. A broad range of medical tasks together with the small training set nature gives meta-learning a big stage to perform. Successfully applications of meta-learning have been demonstrated in medical areas spanning medical image detection and segmentation, medical image diagnosis 12, biomedical image analysis and health informatics.

Meta-Learning Background

Meta-Learning Problem

Traditional machine learning problem optimize the model based on multiple data instances, in contrast, meta-learning model is optimized based on multiple learning episodes, which can be different tasks or the same tasks with different sampling strategies. As shown in table I, compared with other learning strategies, meta-learning will not have negative knowledge transferred, can do rapid online adaptation with few labeled samples, and most importantly, can generalize well to unseen tasks.

| Learning strategy | Transfer knowledge | Rapid online adaptation | No negative transfer | Few labeled samples | Generalize to unseen tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-task learning | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Transfer learning | ✔ | ||||

| Domain generalization | ✔ | ||||

| Domain adaptation | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Lifelong learning | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Meta-learning | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

Meta-Learning Formulation

Supervised Learning

Consider a dataset consisting \(M\) samples: \(\mathcal{D}=\left\{\left(\mathbf{x}_{k}, \mathbf{y}_{k}\right)\right\}_{k=1}^{M}\), where \((\mathbf{x}_k, \mathbf{y}_k)\) is an input-output pair sampled from the joint distribution \(p(\mathcal{X}, \mathcal{Y})\). A task can be specifically defined by learning a model \(f_{\phi}(\mathbf{x}): \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}\) which is parameterized by \(\phi\) to maximize the a posteriori (MAP) estimation for model parameters:

\begin{equation}

\phi^* = \underset{\phi}{\arg \max} \log p(\phi | \mathcal{D})

\label{eq:regular}

\end{equation}

Meta-Learning

The power of meta-learning comes from the knowledge transferring from additional meta-training dataset \(\mathcal{D}_{meta-train} = \{\mathcal{D}_1, \mathcal{D}_2, ..., \mathcal{D}_n\}\) when the number of labeled samples \(K\) is small in dataset \(\mathcal{D}\) (called meta-test dataset). Instead of keeping \(\mathcal{D}_{meta-train}\) in every learning episodes, all prior information from meta-training dataset is extracted and summarized in the new introduced meta-parameters \(\theta\): \begin{equation} \phi^* = \underset{\phi}{\arg \max} \log p(\phi | \mathcal{D}, \theta), \label{eq:learning} \end{equation} where \(\phi^*\) is a task-specific parameters for meta-test task. The meta-learning problem can be formalized as how to learn those meta-parameters \(\theta\) from meta-training dataset:

\begin{equation}

\theta^* = \underset{\phi}{\arg \max} \log p(\theta | \mathcal{D}_{meta-train})

\label{eq:meta-learning}

\end{equation}

Now we defined the objective function of the meta-learning problem, the next question is how to train it? The key idea of training procedure is: training in the same way as testing. Here, the training refers to meta-training (on meta-dataset \(\mathcal{D}_{meta-train}\)) and testing refers to meta-testing (on meta-test dataset \(\mathcal{D}\)). From equation (2), we know that \(\phi^*\) is a function of labeled dataset \(\mathcal{D}\) and meta-parameters \(\theta\), which can be written as: \(\phi^* = g_{\theta}(\mathcal{D})\). The learned task-specific parameters should perform well on the unlabeled dataset \(\mathcal{D}^{test}\) which has the same distribution with \(\mathcal{D}\). A good practice of machine learning training strategy is using cross-validation, where the labeled dataset \(\mathcal{D}\) is splitted into \(\mathcal{D} = \{\mathcal{S}, \mathcal{Q}\}\). Only support set \(\mathcal{S} =\left\{\left(\mathbf{x}_{k}, \mathbf{y}_{k}\right)\right\}_{k=1}^{K}\) is used to optimizer model parameter \(\phi\) while query set \(\mathcal{Q}=\left\{\left(\mathbf{x}_{k}, \mathbf{y}_{k}\right)\right\}_{k=1}^{M-K}\) is used to evaluate the performance of the model. Similar as what we do in the meta-testing, we expect the task-specific parameters \(\phi_i^*\) to have a good performance in each corresponding task on dataset \(\mathcal{D}_i\). Mathematically, the principle of the meta-parameters \(\theta^*\) we want to learn is the one that can give us the best task-specific parameters \(\phi_i^*\) for all corresponding query set \(\mathcal{Q}_i\) after learned on each support set \(\mathcal{S}_i\):

\[\theta^* = \underset{\theta}{\arg \max} \sum_{i=1}^{n} p(\phi_i | \mathcal{Q}_i), \;\; \mathrm{where} \;\; \phi_i = g_{\theta} (\mathcal{S}_i).\]Note that \(g\) is the function that maps labeled dataset to the learner’s parameters \(\phi\), which can be referred to as the learning/adaptation process. \(\theta\) is the meta-parameters which is optimized by the meta-learner.

Approaches Summary

There are three common approaches for meta-learning that mainly differ in how guidance from meta-learner to learner \(p(\phi_i | \mathcal{S}_i, \theta)\) is modeled: black-box adaptation (model-based), optimization-based inference (optimization-based), and non-parametric methods (metric based). The comparison of these three approaches is shown in table II.

| Black-box adaptation | Optimization-based inference | Non-parametric methods | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key idea | Wrap learning process and prediction network in a single pass | Learning process is an optimization problem | Use kernel (metric learning) in prediction |

| Strengthness | + Easy to implement | + Can handle varying/large K | + Computationally fast |

| + Easy to combine with reinforcement learning | + Generalize well to out-of-distribution tasks | + Entirely feedforward | |

| Weakness | - Model and architecture intertwined | - Hard to optimize (second order gradient) | - Classification only |

| - No inductive bias at the initialization | - Hard to scale to large K |

Medical applications applied the first black-box adaptation can be found lung cancer screening (our work) 12. Successfully implementation of optimization-based meta-learning can be found brain cell classification task (our work) 11 and Medical visual question answering 13. Non-parametric meta-learning is popular in many biomedical application such as organ segmentation 14 and rule list of electronic health care records 15.

-

Esteva, Andre, et al. “Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks.” nature 542.7639 (2017): 115-118. ↩

-

Son, Jaemin, et al. “Development and validation of deep learning models for screening multiple abnormal findings in retinal fundus images.” Ophthalmology 127.1 (2020): 85-94. ↩

-

Peng, Yifan, et al. “DeepSeeNet: a deep learning model for automated classification of patient-based age-related macular degeneration severity from color fundus photographs.” Ophthalmology 126.4 (2019): 565-575. ↩ ↩2

-

Ardila, Diego, et al. “End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography.” Nature medicine 25.6 (2019): 954-961. ↩ ↩2

-

Hospedales, Timothy, et al. Meta-learning in neural networks: A survey.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05439 (2020). ↩

-

Finn, Chelsea, Pieter Abbeel, and Sergey Levine. “Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2017. ↩ ↩2

-

Franceschi, Luca, et al. “Bilevel programming for hyperparameter optimization and meta-learning.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2018. ↩ ↩2

-

Hsu, Kyle, Sergey Levine, and Chelsea Finn. “Unsupervised learning via meta-learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.02334 (2018). ↩

-

Nagabandi, Anusha, et al. “Learning to adapt in dynamic, real-world environments through meta-reinforcement learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.11347 (2018). ↩

-

Real, Esteban, et al. “Regularized evolution for image classifier architecture search.” Proceedings of the aaai conference on artificial intelligence. Vol. 33. No. 01. 2019. ↩

-

Yuan, Pengyu, et al. “Few Is Enough: Task-Augmented Active Meta-Learning for Brain Cell Classification.” International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, Cham, 2020. ↩ ↩2

-

Mobiny, Aryan, et al. “Memory-augmented capsule network for adaptable lung nodule classification.” IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (2021). ↩ ↩2

-

Nguyen, Binh D., et al. “Overcoming data limitation in medical visual question answering.” International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Springer, Cham, 2019. ↩

-

Ouyang, Cheng, et al. “Self-supervision with superpixels: Training few-shot medical image segmentation without annotation.” European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, Cham, 2020. ↩

-

Fu, Tianfan, et al. “Pearl: Prototype learning via rule learning.” Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics. 2019. ↩

Comments